Is al-Qaeda on the run or on the march? This question has overshadowed the discourse on terrorism and counterterrorism since the war on terrorism began eight years ago. Last year, it crystallized in a pointed debate over whether the most salient terrorist threat we face is primarily “bottom-up”——that is, from self-selected, self-radicalized “bunches of guys” loosely grouped in entirely independent cells——or if it continues to be posed from the “top down”——by existing, identifiable terrorist organizations actively exploiting the radicalization process for new recruits to whom training, guidance, and direction is then provided.

[1] Recent developments in the United States and two new intelligence assessments from two key European countries firmly fixed in the terrorists’ cross hairs shed further important light on this debate. And, while some disagreement of emphasis will likely persist, what remains incontrovertible is a serious, continuing terrorist threat.

Is al-Qaeda on the run or on the march? This question has overshadowed the discourse on terrorism and counterterrorism since the war on terrorism began eight years ago. Last year, it crystallized in a pointed debate over whether the most salient terrorist threat we face is primarily “bottom-up”——that is, from self-selected, self-radicalized “bunches of guys” loosely grouped in entirely independent cells——or if it continues to be posed from the “top down”——by existing, identifiable terrorist organizations actively exploiting the radicalization process for new recruits to whom training, guidance, and direction is then provided.

[1] Recent developments in the United States and two new intelligence assessments from two key European countries firmly fixed in the terrorists’ cross hairs shed further important light on this debate. And, while some disagreement of emphasis will likely persist, what remains incontrovertible is a serious, continuing terrorist threat.

Four terrorist incidents in as many weeks in the U.S. have re-focused attention on “bottom-up” terrorism——leaderless jihad in the Islam context——often called the “lone wolf” phenomenon in its American variant. The first surfaced in May when FBI agents and New York Police Department (NYPD) officers arrested four men on charges of plotting to bomb two Jewish synagogues in the Bronx, New York and shoot down military aircraft at an upstate Air National Guard base. All but one member of the cell were American-born, U.S. citizens who had served time in prison and were converts to Islam (the fourth man was a Haitian national). Although their ability to actually implement these heinous plans was clearly more in the realm of wishful thinking than bona fide operational capability, the seriousness of their intention was beyond doubt. Authorities described the men as "eager to bring death to Jews" [2] and heralded the arrests as the proof of the need for heightened, ongoing vigilance against an unrelenting menace.[3]

Then, ten days later, a militant opponent of legalized abortion in America gunned down Dr. George Tiller, a Wichita, Kansas medical doctor, who operated a clinic that performed late-term abortions. Three days after Dr. Tiller’s murder, a man who had converted to Islam while imprisoned in Yemen, shot to death one U.S. Army recruiter and seriously wounded another outside an Army-Navy Career Center in Little Rock, Arkansas. And, in mid-June, an 88-year-old white supremacist and virulent anti-Semite fatally wounded a guard at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum before he was himself shot by other officers.

This series of plots and attacks within so brief a time seemed to justify arguments about the salience of “decentralized terrorism” as the main threat now facing the U.S. and perhaps other countries as well. [4] However, two new reports respectively by the British House of Commons Intelligence and Security Committee (ISC) and the Netherlands’ General Intelligence and Security Service (Algemene Inlichtingen en Veiligheidsdienst, or AIVD) paint an alarming picture of the growing dimensions, capabilities, and subversion of Western societies by existing, identifiable terrorist organizations——and specifically by al-Qaeda and its Pakistani jihadi allies.

The House of Commons report, issued in May 2009, follows the seminal official investigation into the 7 July 2005 bombings previously released in May 2006.[5] The new report, titled, Could 7/7 Have Been Prevented? Review of the Intelligence on the London Terrorist Attacks on 7 July 2005,[6] is the most authoritative investigation of the links between the July 2005 attacks and other UK-based al-Qaeda terrorist networks. It focuses on the connections between the London bombers with their would-be counterparts involved in the plot that British authorities dubbed “Operation Crevice”——the plan to bomb a London nightclub (The Ministry of Sound) and a shopping mall in Kent (the Bluewater Shopping Center).

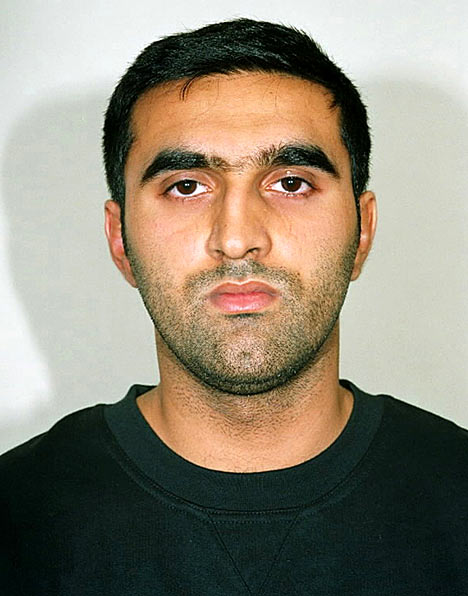

On 30 April 2007, one of the longest terrorist trials in British history concluded with the convictions of five British Muslims[7] charged with plotting to use an explosive device constructed of fertilizer to attack the nightclub and shopping center.”[8] The authorities first became aware of the plot as a result of their identification in 2003 of a British Muslim named Mohammed Qayum Khan (MQK) as an “al-Qaeda facilitator.” MI5 concluded that Khan, a part-time taxi driver residing in Luton, was the leader a UK-based “Al-Qaida facilitation network”——the term that MI5 uses to “refer to groups of extremists who support the Al-Qaida cause and who are involved in providing financial and logistical support, rather than being directly involved in terrorist attack planning.”[9] MI5 had also linked MQK to al-Qaida networks in Pakistan[10] and to the Taliban as well.[11]

Testimony in the trial further revealed that MQK had been “in direct contact with one of Osama bin Laden’s most senior lieutenants”——Abdul Hadi al-Iraqi. A Kurd and former officer in Saddam’s Hussein’s army, Abdul Hadi was described in court as a bin Laden “confidant” and key liaison with the late Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the commander of al-Qaeda in Iraq between 2003 and 2006.[12] According to Muhammed Junaid Babar, whom prosecutors termed a “junior al-Qaeda fixer”[13] who subsequently turned FBI informant, Abdul Hadi was the overall commander of al-Qaeda operations in Britain until his capture in 2007 by U.S. forces in Iraq.[14] Abdul Hadi was the “ultimate emir on top” for the UK jihadis, Babar told court. “But underneath him there were multiple emirs, three or four emirs, before you reached Abdul Hadi, and [MQK] was one of those emirs.”[15] It has been reported that in late 2004 Abdul Hadi met MSK and Tanweer in Pakistan and allegedly “retasked” them to undertake the suicide bombing attack on London’s Underground.[16]

In January 2004, MI5 identified another British Muslim of Pakistani descent named Omar Khyam as the principal courier for MQK’s network[17]. Within a month, however, as a result of continued surveillance of both MQK and Khyam, MI5 concluded, in the words of the ISC report, that they “were no longer looking at a facilitation network providing financial support to Al-Qaida overseas, but had instead found a bomb plot probably aimed at the UK. At this point,” the report continues, “KHYAM became one of MI5’s top targets and Operation CREVICE became their top priority.”[18] MI5 obviously remained intensely interested in MQK as well: who was now regarded as a “trusted member of the CREVICE network.”[19] Still another “significant Al-Qaida-linked facilitator,” involved in fund raising, radicalization, and recruitment in the UK was also identified by the security service but has not been publicly named.[20] These investigations further uncovered at least two other UK-based al-Qaeda networks with direct links back to the organization’s senior command in Pakistan.[21]

As a result of the surveillance mounted as part of Operation Crevice, at least two years before the 7 July 2005 London bombings, MI5 had come across two members of the latter cell. They were its leader, Mohammad Siddique Khan (MSK, who despite the same surname had no family connection to MQK), age 30, and Shahzad Tanweer, age 22.[22] Data obtained from MQK’s mobile telephone revealed several telephone conversations that he had with MSK on at least four occasions——13, 19, and 24 July 2003 and on 17 August 2003. And, Khyam met with both MSK and Tanweer at least three times between February and March 2004.[23]

The Intelligence and Security Committee report also concluded unequivocally that MSK had traveled to Pakistan at least twice for the purposes of receiving training in terrorism and that he very likely had previously visited Afghanistan for the same purpose. In April 2004 an unidentified terrorist detainee had told his interrogators that two men known as “Ibrahim” and “Zubair” had traveled to Pakistan in 2003 for training and met the other members the “Operation Crevice” cell. The two pseudonyms were later conclusively linked to MSK and another person from the Leeds area, named Mohammed Shakil.[24] Hence, it is now clear that MSK made at least two trips to Pakistan for terrorist training: the one referred to previously between November 2004 and February 2005 and another between June and August 2003.[25] Moreover, MQK was described in court documents as having been “instrumental” in arranging for MSK and Tanweer’s first visit in 2003 to the al-Qaeda terrorist training camp in Pakistan’s Malakand Agency.[26] The most consequential trip, however, at least with respect to the 7/7 bombings, was the one that MSK and Tanweer took to Pakistan on 19 November 2004.[27] Both men again returned to the camp in Malakand.[28] Significantly, members of at least two other British Muslim terrorist cells were present at the camp at the same: Mukhtar Said Ibrahim (MSI), the leader of the failed 21 July 2005 suicide bomb plot; and, Abdullah Ahmed Ali, one of the leaders of the August 2006 airline bombing plot.[29]

In sum, rather than the isolated, unconnected outbursts of rage from entirely self-radicalized, self-selected, independently-operating terrorists——which is how British authorities initially described the 7 July 2005 bombing, failed 21 July 2005 attacks, and August 2006 airline bombing plots——a connecting thread directly linking Pakistan to Britain and al-Qaeda to each of these incidents is visible. This incontrovertible evidence was doubtless what Dame Eliza Manningham-Buller, the then-Director General of the British Security Service (MI5) referred to in her landmark November 2006 public address to a London audience. "We are aware of numerous plots to kill people and to damage our economy,” she explained. “What do I mean by numerous? Five? Ten? No, nearer 30 that we currently know of,” Manningham-Buller continued. “These plots often have linked back to al Qaeda in Pakistan and through those links al Qaeda gives guidance and training to its largely British foot soldiers here on an extensive and growing scale.” [30]

The AIVD, the Dutch intelligence and security service, is among the most professional and prescient of the world’s intelligence and security agencies. Its mission is to “safeguard the national security of the Netherlands by identifying threats and risks which are not immediately visible. To this end, it conducts investigations both inside and outside the country.”[32] In sum, the AIVD is responsible for countering non-military threats to Dutch national security; while a military intelligence counterpart concentrates on international threats to the Netherlands from other countries, including espionage. Though far smaller than many of its Western counterparts,[33] the AIVD is an elite and perspicacious service that is as impressive for its early identification and incisive analysis of emerging trends as it appears genuinely able to “think out of the box.” The radicalization phenomenon, for instance——involving homegrown, domestic threats by organizationally unaffiliated militants——that is now so ingrained in our thinking and assessment of contemporary jihadi threats, was first publicly highlighted by the AIVD six years ago in its Annual Report 2002. Thus, as far back as 2001, AIVD agents and analysts had detected increased terrorist recruitment efforts among Muslim youth living in the Netherlands whom it was previously assumed had been assimilated into Dutch society and culture.[34] This assessment was proven tragically correct in November 2003 when a product precisely of this trend that the AIVD had correctly identified, a 17 year-old Dutch-Moroccan youth named Mohammad Bouyeri, brutally murdered the controversial film maker, Theo van Gogh, as he rode his bicycle along an Amsterdam street.[25] Accordingly, any assessment of current jihadi trends by the AIVD is to be taken very seriously, indeed.

The recently released AIVD Annual Report 2008,[36] however, is particularly noteworthy not because of the radicalized individuals it had focused so intently on in the past, but for its emphasis on the growing threat posed by al-Qaeda and other established jihadi organizations. “Local Autonomous networks,” the report argues, “still appeared to be divided and to lack leader figures;” while at the same time highlighting that “Al-Qaeda’s ability to commit and direct terrorist attacks has increased in recent years. The AIVD received a growing number of indications that individuals from Europe are receiving military training at camps in the Pakistan-Afghanistan border region.”[37] Further elucidating this key point, the report goes on to explain how

An analysis conducted in 2008 by the AIVD and verified by fellow services indicates that core Al-Qaeda’s ability to carry out terrorist attacks has increased in recent years. To a great extent, this is explained by the many alliances Al-Qaeda has forged with other networks and groups, both in the Pakistan-Afghanistan border region itself and elsewhere in the Islamic world. . . .

One development of particular concern is the growing evidence that people from Europe are undergoing military training at camps in the border region.[38]

The report’s conclusion is as disquieting as it is sobering: “This could increase the ability of (core) Al-Qaeda and its allies to commit or direct attacks in Europe.” Indeed, these assessments prompted the Dutch National Co-ordinator for Counterterrorism in March 2008 to raise the general threat level for the Netherlands from “limited” to “substantial.”

Both the British ISC and Dutch AIVD reports coupled with the four U.S. incidents provide irrefutable evidence of a continuing and perhaps rising terrorist threat. Each underscores the need not just for eternal vigilance but also for a robust and flexible counterterrorist response. As such, our response capabilities must be as effective at detecting “lone wolves” and decentralized jihadis as it is against more formidable terrorist organizations with the capacity to plan and execute attacks on a potentially grand scale and, moreover, to sustain them as part of a strategic campaign.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

1 See Bruce Hoffman, “The Myth of Grass-Roots Terrorism: Why Osama bin Laden Still Matters,” Foreign Affairs, vol. 87, no. 3, May/June 2008 pp. 133-138; Marc Sageman, ”The Reality of Grass-Roots Terrorism,” and Bruce Hoffman, “Hoffman Replies,” in “Does Osama Still Call the Shots? Debating the Containment of al Qaeda’s Leadership” in Foreign Affairs, vol. 87, no. 4, July/August 2008 pp. 163-166; and, Elaine Sciolino and Eric Schmitt, “A Not Very Private Feud Over Terrorism,” New York Times, 8 June 2008.faced in May when FBI agents

2 Quoted in Susan Candiotti, “Suspects in alleged synagogue bomb plot denied bail,” cnn.com, 21 May 2009 accessed at: http://www.cnn.com/2009/CRIME/05/21/ny.bomb.plot/.

3 Richard Falkenrath, Deputy Commissioner for Counterterrorism, New York Police Department, “Defending the City: NYPD’s Counterterrorism Operations,” Address before the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Washington, DC, 23 June 2009 (transcript by Federal News Service, Washington, DC), p. 6 accessed at ttp://www.washingtoninstitute.org/html/pdf/falkenrath20090623.pdf. at the U.S.

4 See the analysis by the highly respected risk assessment company, Risk Management Solutions, Inc. in RMS, Terrorism Risk Briefing, June 2009 (Newark, CA: Risk Management Solutions, Inc.), June 2009, p. 1.

5 Honourable House of Commons, Report of the Official Account of the Bombings in London on 7th July 2005 (London: The Stationary Office, HC 1087), 11 May 2006.

6 Intelligence and Security Committee, Could 7/7 Have Been Prevented? Review of the Intelligence on the London Terrorist Attacks on 7 July 2005, Cmd 7617, May 20094 Articles a nd Analysis i nSITE| Ju ne 2009

7 Eight persons were initially arrested in the plot of whom five were convicted (Omar Khyam, Jawad Akbar, Salahuddin Amin, Waheed Mahmood, and Anthony Garcia——all were British citizens except for Garcia who was a dual British-Algerian national residing in the UK). Two were acquitted (Shujah Mahmood and Nabeel Hussain) and another person (Mohammed Momin Khawaja) is being tried in Canada. Intelligence and Security Committee, Could 7/7 Have Been Prevented?, p. 11.

8 Operation Crevice has been described as the “largest operation MI5 and the police had ever undertaken.” Some 30 addresses were searched; 45,000 man-hours were consumed by monitoring and transcription; and, 20 surveillance camera operations were mounted involved 34,0000 man-hours. Specific information on the number of covert searches of the suspects’ property and baggage and eavesdropping devices deployed remains classified. Intelligence and Security Committee, Could 7/7 Have Been Prevented?, p. 9.

9 Ibid., p. 7. See also, Ian Cobain and Jeevan Vasagar, “Free——the man accused of being an al-Qaida leader, aka ‘Q’,” Guardian, 1 May 2007; and, Shiv Malik, “The jihadi house parties of hate,” Sunday Times, 6 May 2007.

10 Intelligence and Security Committee, Could 7/7 Have Been Prevented?, p. 29.

11 “Questions over ‘plot mastermind’,” BBC News, 1 May 2007, accessed at http://bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/1/hi/uk/6248803.stm.

12 Cobain and Vasagar, “Free——the man accused of being an al-Qaida leader, aka ‘Q’”; and, Daniel McGrory, Nicola Woolcock, Michael Evans, Sean O’Neill and Zahid Hussain, “Meeting of murderous minds on the backstreets of Lahore,” Times, 1 May 2007.

13 McGrory, et al., “Meeting of murderous minds on the backstreets of Lahore,”; and, Rachel Williams, “July 7 plot accused tell of times with Taliban,” Guardian, 21 May 2008.

14 Cobain and Vasagar, “Free——the man accused of being an al-Qaida leader, aka ‘Q’,” and, Assaf Moghadam, The Globalization of Martyrdom: Al Qaeda, Salafi Jihad, and the Diffusion of Suicide Attacks (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 2008), p. 206.

15 Ibid.

16 See Peter Bergen and Paul Cruickshank, “Al Qaeda-on-Thames: UK Plotters,” Washington Post, 30 April 2007; and, Moghadam, The Globalization of Martyrdom, p. 206.

17 Cobain and Vasagar, “Free——the man accused of being an al-Qaida leader, aka ‘Q’”; and, Intelligence and Security Committee, Could 7/7 Have Been Prevented?, p. 7.

18 Intelligence and Security Committee, Could 7/7 Have Been Prevented?, p. 7.

19 Ibid., p. 29.

20 Ibid., p. 13.

21 Ibid., p. 14.

22 See “The 7/7 bombings: rumours and reality,” Security Service MI5 (no date), accessed at: http://www.mi5.gov.uk/output/the-7-7-bombings-rumours-and-reality.htm; and, “The 7 July bombings and the Security Service,” Security Service MI5 (no date), http://www.mi5.gov.uk/output/the-7-7-bombings-and-the-security-service.html.

23 Intelligence and Security Committee, Could 7/7 Have Been Prevented?, pp. 21-23.

24 Ibid.

25 McGrory, et al., “Meeting of murderous minds on the backstreets of Lahore.”ments as having been “instrumental” in

26 Cobain and Vasagar, “Free——the man accused of being an al-Qaida leader, aka ‘Q’”; and, Malik, “My brother the bomber.”

27 Mark Kukis, With Friends Like These...,” New Republic, 20 February 2006.

28 “Suicide bombers’ ‘ordinary lives’,” BBC News, 18 July 2005 accessed at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/4678837.stm.

29 Sean O’Neill, “Analysis: How the plan was put together; Little did Ahmed Ali and his cohorts know that they were under round-the-clock surveillance while plotting their attacks,” Times, 9 September 2008. See also Gordon Corera, “Bomb plot——the al-Qaeda connection,” BBC News, 9 September 2008 accessed at http://bbc.co.uk/go/pr/fr/-/2/hi/uk_news/7606107.stm; Duncan Gardham, “Airliner bomb trial: George W. Bush took decision that triggered arrests,” Telegraph, 8 September 2008; and, David Leppard, “Fixer for 21/7 plot free in London,” The Sunday Times, 15 July 2007.

30 See also, Peter Bergen, “Where You Bin?,” New Republic, 29 January 2007 accessed at: http://www.lawandsecurity.org/get_article/?id=64; Bergen and Cruickshank, “Al Qaeda-on-Thames”; Steve Coll and Susan B. Glasser “In London, Islamic Radicals Found a Haven,” Washington Post, 10 July 2005; Gordon Corera, “were bombers linked to al-Qaeda,” BBC News, 6 July 2006 accessed at http://newsvote.

bbc.co.uk/mpapps/pagetools/print/news.bbc.c.uk/2/hi/uk_news/5156592/6065460.stm; Rosie Cowan and Richard Norton-Taylor, “Britain now No 1 al-Qaida target——anti-terror chiefs,” Guardian, 19 October 2006; Margaret Gilmore and Gordon Corera, “UK ‘number one al-Qaeda target’,” BBC News, 19 October 2006 accessed at: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/6065460.stm; Mohammed Khan and Carlotta Gall, “Accounts After 2005 London Bombings Point to Al Qaeda Role From Pakistan,” New York Times, 13 August 2006; and, Moghadam, The Globalization of Martyrdom, p. 207.

31 Quoted in BBC News, “Extracts from MI5 Chief’s Speech,” November 10, 2006 accessed at http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk/mpapps/pagetools/print/news.bbc.co.uk/2/hl/news/6135000.stm.

32 General Intelligence and Security Service, Annual Report 2007 (The Hague: Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, 2008), p. 1.

33 The AIVD reportedly employs some 1,100 people. See DutchNews LG accessed at: http://www.dutchnews.nl/dictionary/2006/11/aivd.php.

34 General Intelligence and Security Service, Recruitment for the Jihad in the Netherlands: From Incident to Trend (The Hague: Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, December 2002).

35 See the excellent book by Ian Buruma, Murder in Amsterdam: Liberal Europe, Islam, and the Limits of Tolerence (London & New York, Penguin, 2007),

36 General Intelligence and Security Service, Annual Report 2008 (The Hague: Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, 2009).

37 Ibid., p. 17.

38 Ibid., p. 19.

39 Ibid., p. 17.

40 Ibid., p. 18.