Resisting the Caliphate

Earlier, I posted on the declaration by the Islamic State (IS)—formerly known as the Islamic State in Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS)—of a Caliphate that included territory in both Iraq and Syria. The post made several points about this momentous event, including the real potential for resistance from both ordinary Iraqis and other militant groups. As I noted then, everywhere that IS has attempted to implement their extremist version of shari’a on ordinary Muslims who do not support or affirm IS’s vision for the future of Islam, have fought against the militants.

Now, multiple reports from Iraq and Syria suggest that resistance to IS might have begun, but that this has not prevented IS from making new gains and opening new fronts in their war. The skirmishing started in Mosul with the killing of several members of IS by unknown snipers, and the announcement of a resistance group called the Mosul Brigades. A local fighter claimed that the core of one of the armed brigades consisted of former military officers, the very people who constituted the earliest resistance in the Iraqi guerrilla war against the United States. A few days later, clashes broke out between IS and another part of the coalition that has been battling the government of Iraq, the Army of the Men of the Naqshabandiyya Order (JRNT), reportedly led by former Saddam-era regime official, ‘Izzat Ibrahim al-Duri.

Meanwhile, discontented tribesmen in Syria have risen against IS in Dayr al-Zawr, an area of Syria that IS seized only a few weeks ago from other rebel groups. After fierce fighting and suffering serious casualties, IS was forced to withdraw from several villages. The main source of resistance seems to be the Shu’aytat tribe, which has been tweeting that it started the uprising against the State. Other reports emphasize that the fighting is more than just one tribe and assert that the entire area is about to begin a popular revolt against the “criminals” and “Khawarij”—a common term for extremists who hold the views of al-Qaeda (AQ) and ideologically affiliated groups.

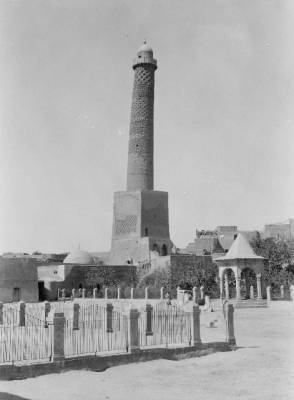

The reasons for resistance to IS might, at least on the surface, seem unrelated. The residents of Mosul are angry about two separate policies carried out by IS: the treatment of Christians and the destruction of the cultural treasures of the city. Not long after taking Mosul, IS gave Christians the three choices demanded by their extremist version of shari’a: pay a discriminatory tax, convert to Islam, or be killed. The organization also began a systematic demolition of churches throughout Mosul. Despite the brutality already demonstrated by IS, Muslim residents of Mosul promised to protect their Christian neighbors, but to no avail: most of the Christian population fled the city in fear. The destruction of churches, shrines, mosques, and the tomb of Jonah also incensed Mosulis, who believe that the Islamic State is obliterating the history and culture of the city. The very first sign of physical resistance to IS was, in fact, when IS members attempted to blow up “Al-Hadba,” an ancient “leaning” minaret that is the signature landmark for the city. Nearby residents formed a human chain and prevented the extremists from planting explosives in the 840-year old structure.

The fighting in Syria, on the other hand, was set off by tribal unrest against IS authority and started with the arrests of Shu’aytat tribesmen by IS gunmen. Members of the tribe, angered at this treatment, said that the Shu’aytat had been humiliated by the extremists, and began attacking police stations and other centers of control in the villages. Some reports suggest as well that the decision to assault IS might have been influenced by the fact that the tribe had benefitted from selling oil before the IS takeover and hoped to expel the interlopers so that they could maintain their livelihood.

Despite the surface disjuncture between these two outbreaks of opposition to IS, there is a common theme to both: the brutality and intransigence of the IS style of governance. In an earlier quarrel with AQ, the IS spokesman argued that their extremist version of shari’a had to be imposed in its entirety and that IS would not attempt to “win hearts and minds.” To their dubious credit, IS has lived up to this declaration. The specific version of shari’a that IS espouses is even more extreme than that of AQ, and the targeting of Shi’a and Christians, destruction of all signs of “innovation” (the term this version of shari’a uses for sites like shrines, mosques, or tombs that are highly venerated by Muslims), and refusal to compromise with local tribesmen (who should know that “shari’a” and not the old tribal customs are what will matter in the new order), all flow naturally from this extremist set of laws. In fact, the IS statement on the fighting in Dayr al-Zawr specifically said that “the State is governed by shari’a, and not by tribalism.”

It is clear from these incidents that IS has failed to learn from their previous experience of shadow governance in Iraq (2006-2007), when local tribes were provoked into rising against the extremists for precisely the same reasons. It is also clear that there is no guarantee that a local uprising—on its own—will be able to stop the group. Despite what some have said, the “Awakenings” were incapable of defeating ISI (as the organization was then known): rather, it was the combination of local resistance and U.S. boots on the ground, fighting a sophisticated counterinsurgency, that caused the collapse of the previous incarnation of these same extremists and rolled back their gains. Recent reports of advances by IS in Iraq suggest that the current fighting is far from over and IS is far from defeated. Only time will tell whether Iraqis and Syrians—without outside assistance—can effectively resist the military juggernaut that IS seems to have become.