Al-Qaeda and Pakistan: The Evidence of the Abbottabad Documents (Part Three)

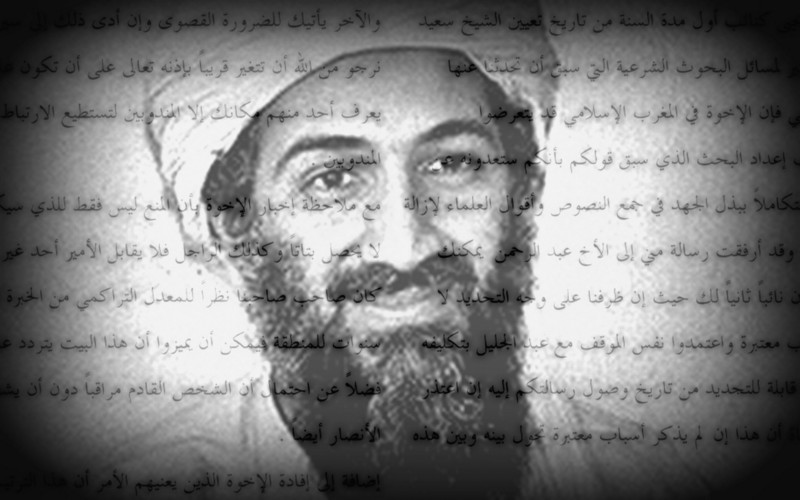

The release last month of eight new documents, captured during the raid that killed Usama bin Laden, is allowing us to re-examine conclusions reached earlier about al-Qaeda (AQ). Two previous posts used the new evidence to look at the relationship between AQ’s leadership and affiliates, and at Bin Laden’s involvement in running his own organization. This post examines what the documents have to say about the complex relationship between AQ and Pakistan.

Ever since Bin Laden was found in Abbottabad, living in a lavish mansion not far from a large Pakistani military establishment, there have been suspicions of Pakistani complicity—in some capacity—with AQ. The U.S. government has been quite clear that, as one official put it, they had no evidence “Kayani or other top Pakistani officials knew of Bin Laden’s presence…” A thorough search of the document treasure trove captured during the raid also found “no smoking gun on Pakistani complicity.” These conclusions are backed up by the first seventeen documents declassified from the Abbottabad raid, which say nothing about the relationship between Pakistan and AQ.

Ever since Bin Laden was found in Abbottabad, living in a lavish mansion not far from a large Pakistani military establishment, there have been suspicions of Pakistani complicity—in some capacity—with AQ. The U.S. government has been quite clear that, as one official put it, they had no evidence “Kayani or other top Pakistani officials knew of Bin Laden’s presence…” A thorough search of the document treasure trove captured during the raid also found “no smoking gun on Pakistani complicity.” These conclusions are backed up by the first seventeen documents declassified from the Abbottabad raid, which say nothing about the relationship between Pakistan and AQ.

Three of the just-released documents do, however, have something new to say on this issue, offering some interesting evidence about the complicated links between AQ and at least parts of the Pakistani state. The three are letters between Bin Laden and ‘Atiyya Abd al-Rahman, his chief of staff, forming a nearly complete record of their correspondence from June to August 2010. The first letter—from ‘Atiyya to Bin Laden and dated 19 June 2010—mentions, among dozens of other matters, that he had been in contact with the Pakistanis (at times through couriers) to warn them to leave the group alone. If they did so, AQ would leave the Pakistanis alone, instead focusing on fighting the Americans in Afghanistan. Specifically, AQ told the Pakistanis not to do them harm, to leave them be, and not to cooperate with the Americans in their “espionage war” against AQ or else AQ would carry out attacks against them inside their country. The intermediaries used by AQ to convey this message are described as “jihadists who have relations with the state, the government, intelligence services, and others.”

The second letter—also from ‘Atiyya to Bin Laden and dated about a month later—is obviously in reply to a letter from Bin Laden that we do not have. Among the responses to questions apparently posed by Bin Laden, ‘Atiyya provides more details about the negotiations with the Pakistanis. Most importantly, he notes that “intelligence leaders,” including “Shuja Shah”—thought to be the head of Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) at the time, Ahmad Shuja Pasha (his real last name is “Shah”; “Pasha” is an honorific)—directly sent a letter to AQ to explore the possibility of talks. Then, “the intelligence people” reached out multiple times to AQ through, in ‘Atiyya’s description, “some of the Pakistani ‘jihadist’ groups, the ones that they approve of.” ‘Atiyya specifically names Harakat al-Mujahidin, a group linked to AQ, and notes with surprise that the head of the group, Fadl al-Rahman Khalil (who signed the original AQ declaration of jihad against the U.S. in 1998), showed up personally to act as a representative for the Pakistanis.

The TTP is, in other words, treated here as just another subordinate affiliate of AQ, with AQ central leadership taking the lead and with the affiliate having a responsibility to report up the chain of command.

‘Atiyya also says that the negotiations involved Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) (Hakimullah’s group) from the outset, making clear that the two supposedly separate organizations dealt with the negotiations as one. After the first approach by the Pakistanis, the two discussed matters internally and then consulted with Zawahiri (here called “Abu Muhammad”) before responding with their negotiating position. ‘Atiyya asserts as well that the Chief Minister of Punjab, Shahbaz Sharif, sent a note to AQ—which ‘Atiyya passed on to the TTP—asking about negotiations. This is significant for several reasons, but most importantly, it shows that Pakistani authorities understood the close ties between AQ and TTP well enough to approach those they considered to be in charge (i.e. AQ, rather than TTP). This view of the relationship is supported by ‘Atiyya, who says, “We stressed that they [TTP] needed to consult us on everything, and they promised they would. In the last meeting I had with Hakimullah I asked about it. He said there was nothing new and that he would report anything new to you [i.e. Bin Laden; emphasis added].” The TTP is, in other words, treated here as just another subordinate affiliate of AQ, with AQ central leadership taking the lead and with the affiliate having a responsibility to report up the chain of command.

Finally, the third letter is an apparent reply to this note, with just a quick sentence from Bin Laden on AQ Pakistan policy: “In regards to the truce with the Pakistani government, continuing the negotiations in the way you described is in the interest of the mujahidin at this time.” The term used here by Bin Laden for the goal of the talks is a “hudna,” which implies a temporary ceasefire in order to prepare for further hostilities, rather than the more permanent “sulh” (peace). The entire series of letters is, in fact, full of mistrust and disdain for the Pakistani government, military, and intelligence services, with no hint that some sort of deeper or more stable understanding was possible between the two sides.

Yet, this level of negotiations is far more than has previously been acknowledged to exist when describing the relationship between AQ and Pakistan. The most that has been disclosed appeared early on in reporting by the New York Times from late May 2011. According to the article, documents seized in Abbottabad show Bin Laden and “his aides” had discussed making a deal with Pakistan. The article then describes an arrangement that is very similar to that portrayed in the newly released letters: AQ would foreswear attacking the country in exchange for protection inside Pakistan.

The three new letters make it clear that Pakistani military and intelligence personnel—as well as at least one mid-ranking government authority—were indeed exploring talks with AQ, at times through intermediaries, in an attempt to prevent violence in their own country.

There is, however, one very big difference: according to the “officials” quoted in the article, the proposal never went beyond a “discussion phase” and the officials said that there was no evidence the matter was ever raised with Pakistani military or intelligence personnel. The three new letters make it clear that Pakistani military and intelligence personnel—as well as at least one mid-ranking government authority—were indeed exploring talks with AQ, at times through intermediaries, in an attempt to prevent violence in their own country.

There is, however, no new evidence suggesting the involvement of other parts of the Pakistani state. It is also important to stress that AQ saw their dealings with Pakistani officials as a necessary evil: Pakistan was still the enemy; they had no intention of working more closely with the leaders of that country; and would negotiate only a “ceasefire” in a war they had every intention of continuing at some point in the future.