ISIS is Doubling Down on The Philippines

In August, I wrote an analysis on an increasingly evident aim by the Islamic State (ISIS) “to establish a more substantial base in the Philippines.” My assessment was based on recent events in the country, the most notable of which being the July 31 suicide bombing by Moroccan fighter “Abu Kathir al-Maghrebi” on Basilan island, which ISIS claimed. The attack was a landmark event for the Philippines: for the first time, a foreigner fighter from outside of the Southeast Asia region had been attributed to an attack in the Philippines—the first suicide operation there, at that.

Abu Kathir’s nationality, the use of a car bomb, along with ISIS media’s timely claim and promotion, were all red flags signaling that ISIS was looking to gain a footing there. Two months later, this is only looking more so to be the case.

Among the most outwardly troubling elements for the Philippines is that foreign fighters like Abu Kathir seem to be becoming less of an anomaly. On September 22, the Philippines’ Bureau of Immigration (BI) blocked the entry of an 36 year old Pakistani ISIS trainer named Naeem Hussain, who had reportedly attempted to enter the country via a flight from Dubai. According to a BI official, the man had also attempted to enter the country this past May via Ninoy Aquino International Airport.

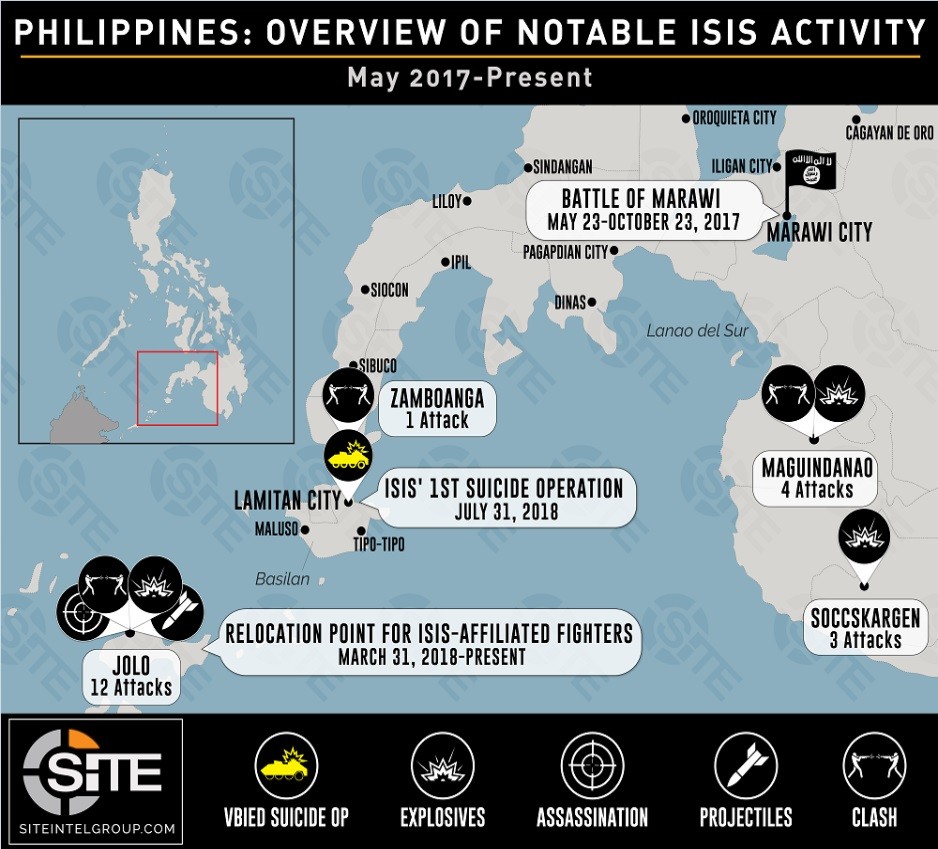

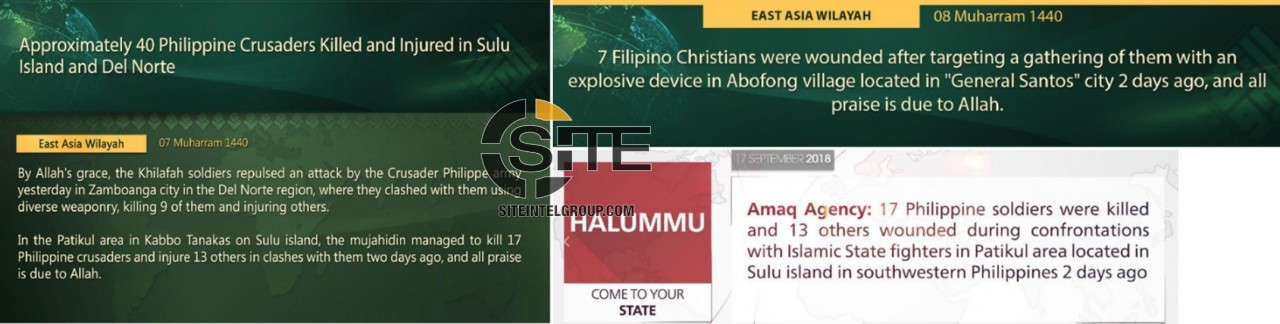

This alleged trainer’s arrest comes as ISIS-claimed operations are reaching further across the Philippines. Of the 10 operations claimed since Abu Kathir’s July 31 attack, eight have spanned out from its foothold in Sulu into the regions of Maguindanao, Soccskargen, and Zamboanga.

A map of notable ISIS activity in the Philippines since May of last year follows:

ISIS’ play for the Philippines isn’t only evident in these attacks; there is a corresponding and equally critical media and outreach component to ISIS’ game-plan.

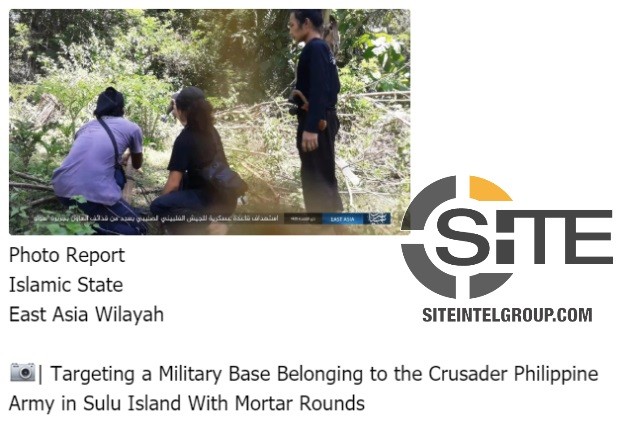

On August 9, just 10 days after Abu Kathir’s attack, ISIS announced the creation of the East Asia Wilayah (Province) via a photo report of fighters firing mortar rounds at a "military base for the Crusader Philippine army" in Sulu.

At face-value, ISIS’ establishment of a “province” seems like a simple affair—a cheap hype move to perpetuate its pretensions of statehood while distracting from its losses in Iraq and Syria. Such assessments would be at least somewhat true. ISIS has been promoting the Philippines for over three years now through videos, articles, interviews, and attacks, urging followers from around the world to join its fighters in the country.

At face-value, ISIS’ establishment of a “province” seems like a simple affair—a cheap hype move to perpetuate its pretensions of statehood while distracting from its losses in Iraq and Syria. Such assessments would be at least somewhat true. ISIS has been promoting the Philippines for over three years now through videos, articles, interviews, and attacks, urging followers from around the world to join its fighters in the country.

However, at no point in these years did ISIS ever establish an East Asia Province. Even during ISIS fighters’ siege on Marawi between May and October of last year, which was the group's most opportune time to capitalize on hype in the region, ISIS still did not do so. Instead, the group waited until August, almost a year after the Marawi siege and four years after pledges to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi began coming out of the Philippines.

Why?

Establishing an ISIS “province” requires more conditions than carrying out attacks.

On messenger applications and social media platforms, pro-ISIS channels and groups in Southeast Asia languages are likewise thriving, translating ISIS media, inciting for attacks, and soliciting donations.

A functioning ISIS "province" requires an organized and centralized media operation from the region. That said, during the Marawi siege, the vast majority of media output and attack updates came not from ISIS, but from fighters and ISIS operatives on Telegram. ISIS did issue updates and video footage via its 'Amaq News Agency, but with significant delay and far less frequency. Without the direct communication channels needed for a centralized media operation, ISIS' Philippines news updates were old by the time it issued them.

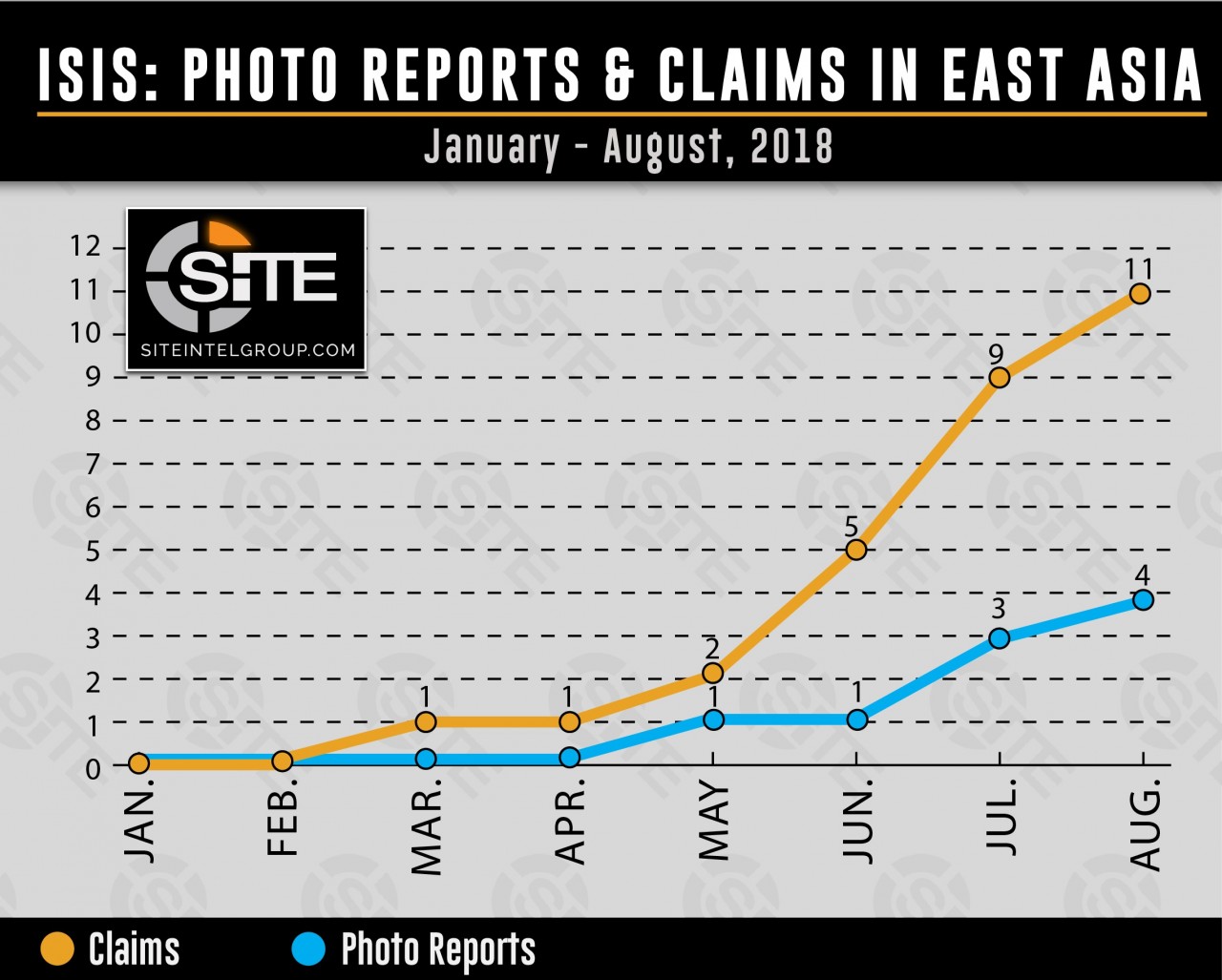

Indeed, it wasn't until the apparent establishment of solid communication channels between the Philippines and ISIS central that the group would announce its so-called East Asia Province. During the five months between January and May of 2018, ISIS issued three claims from the Philippines; but between June and July, the two months leading to the announcement of its East Asia Province, ISIS issued 10 claims from the region, following up with seven in August.

As the group’s military activities have increased, so has its photo report production. While only publishing one photo report between January and May, ISIS issued four photo reports between June and July. The same number was seen in August. Now, for the first time, ISIS media was systematically streaming out of the Philippines via the group's official channels. The following graph shows the simultaneous increase of photo reports and operation claims from ISIS out of East Asia:

Such media has included disturbing photo reports featuring kids. One ISIS photo report, entitled, “Diaries of a Mujahid in East Asia Province,” shows the daily lives of fighters, among whom are children.

These warning signs coming out of Southeast Asia are growing: migrant fighters, expanding geographic ranges of attacks, and increases in regionally targeted media. On messenger applications and social media platforms, pro-ISIS channels and groups in Southeast Asia languages are likewise thriving, translating ISIS media, inciting for attacks, and soliciting donations. These elements should not be seen not as isolated elements, but as connected steps toward a blatant goal to establish a footing in the Philippines. That said, it is imperative that these developments be reported on and addressed as such—not just for the Philippines, but the entire Southeast Asia region.